What wavelength are we actually on?

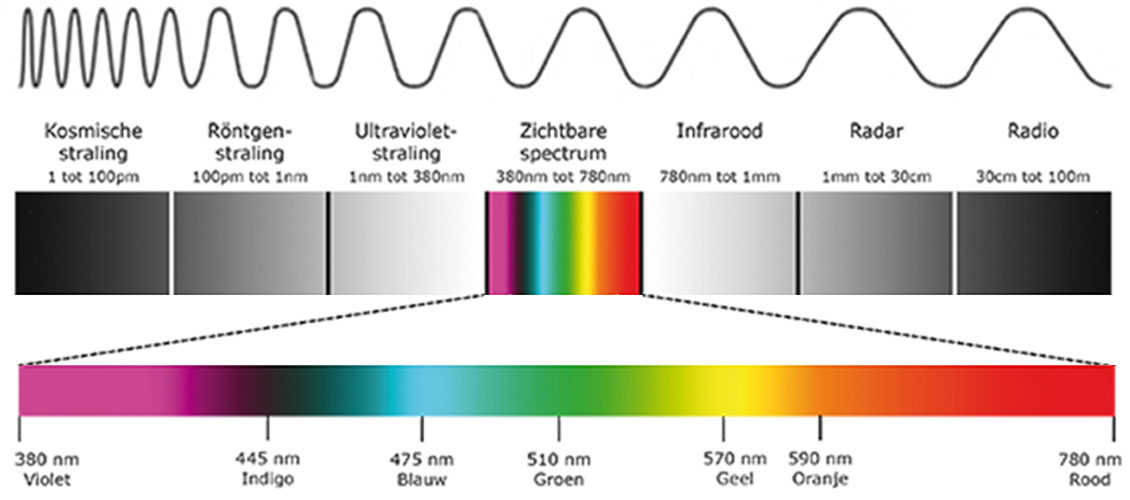

Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation, and the part we perceive as color is known as visible light. This visible light has a wavelength between approximately 380 nanometers (violet) and 780 nanometers (red). These wavelengths determine what colors our eyes can see — and that’s far more than a screen or printer can reproduce. That’s why color differences often arise between what you see on screen and the final print, especially if you’re not using a properly set photo color profile.

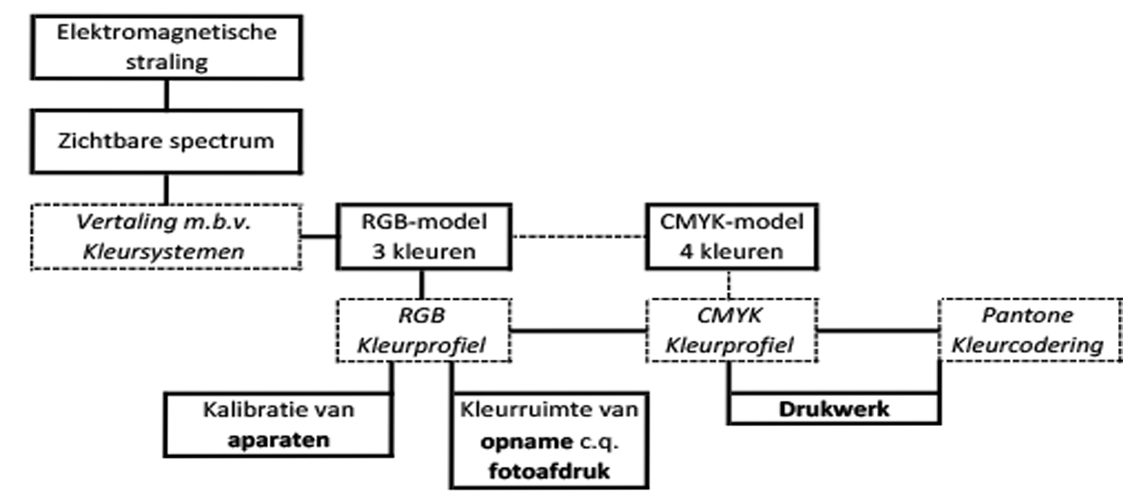

To reproduce colors technically, we use two models. The RGB model (Red, Green, Blue) is used for screens, cameras, and digital files. For printed materials and photo prints, the CMYK model (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Key/Black) is used. With a solid understanding of photographic color theory and human color perception, you can streamline your workflow to ensure your prints match your digital image as closely as possible.

From Light to Pixels: How a Camera ‘Translates’ Color

When you take a photo, your camera’s sensor captures light. That light consists of electromagnetic radiation within the visible spectrum: the part we experience as color. The sensor perceives that radiation as raw data, which is then converted into pixels with color information.

This conversion can happen in two ways. If you shoot in JPG, the camera does this translation directly. If you work in RAW, the raw information is only converted later on the computer. In both cases, the color profile determines how the colors are displayed.

Not only does the camera color profile play a role, your monitor also has its own profile. When editing photos, it’s important that your screen is properly calibrated. This ensures that colors are displayed as accurately as possible, which is essential if you also want to print your photos. A calibrated screen ensures that you and others see the photo as you intended it.

Eye versus color profile

When taking the shot, you should actually already be aware of the color profile you’re shooting in. Series you have high expectations for are best shot in RAW, because that’s where the color information maintains the best quality: the image in RAW is still purely the sensor’s registration, giving the translation from your eye to a picture the best start. RAW does take up more space, so you can also choose to photograph vacation photos in JPG, for example, and only switch to RAW for special moments.

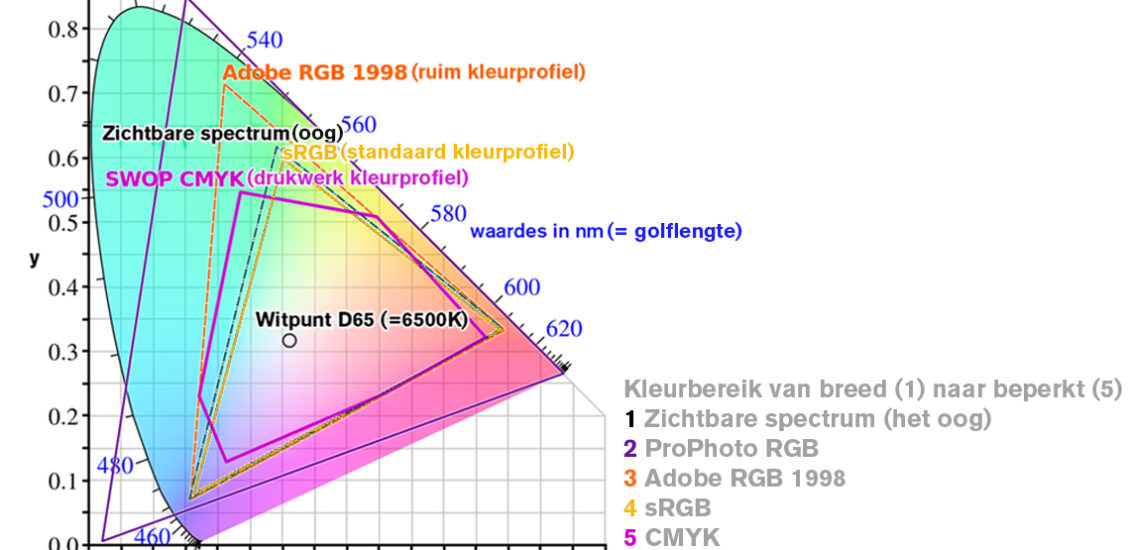

For photochemical prints, you usually deliver your files in AdobeRGB or sRGB. AdobeRGB has a wider color gamut than sRGB and is therefore suitable for professional print work. ProPhotoRGB, once developed by Kodak to encompass virtually all colors in nature, is even wider but also less practical. This profile contains colors that fall outside the range of printers and monitors, which means using it for prints or on screen can actually lead to inaccuracies.

If you shoot in JPG, it’s best to choose AdobeRGB. If you publish your photos online, it’s wise to convert them to sRGB. This profile better matches color display and prevents color shifts on the internet.

In the table below, you can see how the eye compares to the most well-known color profiles.

Eye versus print

Different printing techniques can give different results. To properly predict what the final result will be, there are several factors you need to consider. In photography, it starts with properly setting the white balance on the camera and a correctly configured computer screen. To complete the circle, you can also download our color profiles from the website to set up a soft proof. Soft proofing is simulating a print on the monitor, which of course only makes sense if the screen is properly configured. When you display the photo via the soft proof, the result can sometimes be disappointing. Especially bright colors, such as bright red or bright green, can fall short.

To a certain extent, you can still adjust your post-processing to bring the final effect closer to the mood you want to convey, but sometimes a certain color simply isn’t achievable. You can then decide whether you still want to print that image or prefer to select another photo to display large on the wall.

Simulating the effect of various paper surfaces remains something that’s difficult; a screen emits light and paper doesn’t… Everything revolves around learning to understand what you actually see on screen and how that translates to a print.

Can you calibrate your eyes?

Besides the technical limitations of color reproduction, there’s something else at play: your own eyes. Everyone sees colors just a little differently. The way you experience an image is personal, and that’s what makes photography so fascinating. Eyes can’t be calibrated like you can do with a screen. Fortunately, because that variation ensures that not everyone has the same preference. Some love subtle tones, others prefer powerful contrasts. Some have a sharp eye for color and style, while others prefer working in black and white.

With a beautiful print on the wall or a photo book on the coffee table, we can continue to surprise each other with our perspective on things, keeping the world colorful and diverse. So feed your eyes and catch those rays!